Spanish Flu Vaccines -- A pro-vax-friendly research guide

There’s an unconfirmed rumor going around that we had flu vaccines during the deadly Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. How should a savvy internet researcher and devotee of vaccine science proceed?

Step 1: Apply common sense & form a hypothesis

The rumor sounds bogus—we didn’t even know what caused the flu in 1918, so how could we have had vaccines?

Today, we know all about the flu—except why most people who have it test negative for any flu virus (1). Other than not knowing why most people don’t have the virus that made them sick, we know all about the flu, and we have vaccines for it.

But those vaccines weren’t invented until the 1940s, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). And the CDC’s timeline for the Spanish Flu pandemic doesn’t say anything about vaccines.

Hypothesis: The rumor of vaccines for Spanish Flu is probably a conspiracy theory, invented by anti-vaxxers to discredit vaccination and terrify the vaccine-hesitant.

Step 2: Consult multiple credible sources & form a conclusion

Here’s what the web has to say about Spanish Flu vaccines:

From the Centers for Disease Control: “The 1918 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. … With no vaccine to protect against influenza infection and no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections that can be associated with influenza infections, control efforts worldwide were limited to non-pharmaceutical interventions…”

From the National Archives: “In the United States, a quarter of the population caught the virus, 675,000 died, and life expectancy dropped by 12 years. With no vaccine to protect against the virus, people were urged to isolate, quarantine, practice good personal hygiene, and limit social interaction.”

From Reuter’s: “The claim that the influenza pandemic of 1918 ‘was the after-effect of the massive nation-wide vaccine campaign’ is unfounded. A vaccine against the flu did not exist at the time.” The article is dated April 1, 2020, but there’s no indication it’s a joke.

From History Channel: “The 1918 flu was first observed in Europe, the United States and parts of Asia before swiftly spreading around the world. At the time, there were no effective drugs or vaccines to treat this killer flu strain.”

So, we have 4 credible sources that all agree there were no Spanish Flu vaccines.

Conclusion: The rumor that we had vaccines for the deadly Spanish Flu is a conspiracy theory invented by anti-vaxxers to discredit vaccines and terrify the vaccine-hesitant.

***

NOTE: It’s perfectly acceptable, and even encouraged, to stop your investigation at this point—especially if you’re vaccine hesitant. If you’ve gotten this far, you can confidently say you’ve done your due diligence.

***

Step 3 (Optional): Dig deeper & apply logic

Anti-vaccine disinformation is getting more and more sophisticated, making easy prey of the vulnerable vaccine hesitant.

Often, anti-vaccine propaganda looks suspiciously like a scholarly paper; it may contain multiple citations and references, and may even be published in a respected medical journal. Until it’s retracted or disappeared, don’t be fooled by all the trappings of legitimacy.

Here’s an example—a paper entitled The State of Science, Microbiology, and Vaccines Circa 1918 by J.M. Eyler, published in the journal Public Health Reports in 2010 (2):

“Published since 1878, Public Health Reports is the official journal of the Office of the U.S. Surgeon General and the U.S. Public Health Service. It is published bimonthly, plus supplement issues, through an official agreement with the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. The journal is peer-reviewed and publishes original research, reviews, and commentaries related to public health practice and methodology, public health law, and teaching at schools and programs of public health. Journal Issues include regular commentaries by the U.S. Surgeon General and the executives of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health.”

According to the paper:

“Many vaccines were developed and used during the 1918–1919 pandemic. The medical literature was full of contradictory claims of their success; there was apparently no consensus on how to judge the reported results of these vaccine trials.”

Since we already confirmed with multiple credible sources that there were no vaccines for Spanish Flu, the author is apparently an anti-vaccine activist, who tricked a respected professional journal into publishing a nonsense paper to discredit vaccination—the greatest medical miracle of all time.

The paper claims vaccines for Spanish Flu not only existed in 1918, but millions were widely distributed, completely unregulated, and generally less than miraculous.

The vaccine market Eyler describes sounds a lot like a wild-west circus of snake-oil salesmen—with some vaccines developed, tested and brought to market within mere days. Obviously the dignified medical experts of the day would never have behaved so recklessly.

The following excerpts from the paper describe Eyler’s fictional world of Spanish Flu vaccines, where prominent medical authorities pontificated about nonsense causes and cures, and created strange new vaccines on a wing and a prayer, with the hope and promise of profit.

NOTE: This scenario bears no resemblance whatsoever to the COVID19 pandemic.

“Richard Pfeiffer announced in 1892 and 1893 that he had discovered influenza’s cause. Pfeiffer’s bacillus (Bacillus influenzae) was a major focus of attention and some controversy between 1892 and 1920. The role this organism or these organisms played in influenza dominated medical discussion during the great pandemic.”

“The fate of Pfeiffer’s bacillus as the probable cause of influenza is reflected in the use of vaccines in the United States during the pandemic of 1918–1919. … Those who already had a vaccine in hand were quick off the mark to promote their vaccines as sure preventives or cures for influenza. Drug manufacturers aggressively promoted their stock vaccines for colds, grippe, and flu. These vaccines were of undisclosed composition. As public anxiety and demand swelled, there were complaints of price gouging and kickbacks. Preexisting vaccines of undisclosed composition were also endorsed by physicians such as M.J. Exner, who actively promoted in newspaper interviews and testimonials the vaccine developed some six years earlier by his colleague, Ellis Bonime. … His vaccine was claimed to prevent pneumonia, influenza, and blood poisoning.”

“On October 2, 1918, Royal S. Copeland, Health Commissioner of New York City, sought to reassure citizens that help was on the way, because the director of the Health Department’s laboratories, William H. Park, was developing a vaccine that would offer protection against this dreaded disease.”

“Park’s was not the only Pfeiffer’s bacillus influenza vaccine to make an early appearance during the pandemic. At Tufts Medical School in Boston, Timothy Leary, professor of bacteriology and pathology, developed another Pfeiffer’s bacillus vaccine. … Leary promoted his vaccine as both a preventive and a treatment for influenza. Other Pfeiffer’s bacillus vaccines soon followed. Faculty from the Medical School of the University of Pittsburgh isolated 13 strains of the Pfeiffer’s bacillus and produced a vaccine from them by modifying the techniques Park had used. In the crisis atmosphere of the pandemic, the Pittsburgh vaccine developers isolated their strains, prepared the vaccine, tested it for toxicity in some laboratory animals and in two humans, and turned it over to the Red Cross for use in humans—all in one week. In New Orleans, Charles W. Duval and William H. Harris from Tulane University’s Department of Pathology and Bacteriology developed their own chemically killed Pfeiffer’s bacillus vaccine.”

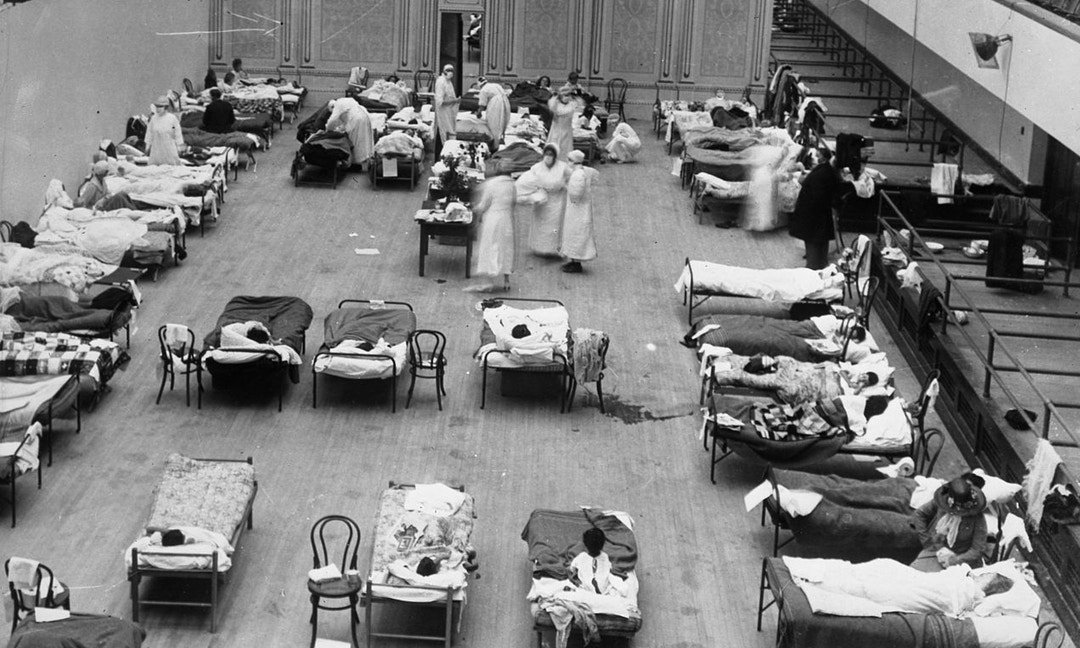

This looks eerily familiar. Could it be a Spanish Flu vaccine line?

“It was not only heads of bacteriological laboratories who acted on the assumption that Pfeiffer’s bacillus was the cause of influenza and developed vaccines on that assumption. Some private physicians did the same. Horace Greeley of Brooklyn, New York, reported isolating 17 strains of the bacillus from 17 patients, and from these ‘strains,’ he developed a heat-killed vaccine intended to be administered in three increasing doses. With it he immunized his own patients, and he distributed eight liters to colleagues who did the same.”

“These vaccines were widely used. Park’s vaccine was released to the military for use in Army camps as well as to private physicians. It was also used as corporate policy among industrial workers, including the 14,000 employees of the Consolidated Gas Company and 275,000 employees of the U.S. Steel Company. Leary’s vaccine was used frequently during the epidemic in state custodial institutions of the Northeast and by some private physicians. Duval and Harris reported immunizing approximately 5,000 people, most of whom were employees of large New Orleans companies. Almost without exception, those reporting on the use of these Pfeiffer’s bacillus vaccines reported that they were effective in preventing influenza.”

“As confidence in the role of Pfeiffer’s bacillus in influenza waned, the strategy of prevention by vaccine changed. Vaccines developed later in the pandemic—and almost all developed in the middle of the country and on the West Coast—were composed of other organisms either singly or in mixtures. Increasingly, vaccines were justified as preventing the pneumonias that accompanied influenza. Killed streptococci vaccines were developed by a physician in Denver and by the medical staff of the Puget Sound Naval Yard. The latter was used among sailors and also among civilians in Seattle.”

“Mixed vaccines were more common. These typically contained pneumococci and streptococci. Sometimes staphylococci, Pfeiffer’s bacillus, and even unidentified organisms recently isolated in the ward or morgue were included. The most widely used, and historically the most interesting, was the vaccine produced by Edward C. Rosenow of the Mayo Clinic’s Division of Experimental Bacteriology. Rosenow argued that the exact composition of a vaccine intended to prevent pneumonia had to match the distribution of the lung-infecting microbes then in circulation. The Mayo Clinic distributed Rosenow’s vaccine widely to physicians in the upper Midwest. No one seems to know for sure how many people received this vaccine, but, through physicians, Rosenow received returns for 93,000 people who had received all three injections, 23,000 who had received two injections, and 27,000 who had received one. Rosenow’s vaccine received even wider distribution. It was adopted by the City of Chicago. The Laboratories of the Chicago Health Department produced more than 500,000 doses of the vaccine. Some of it was distributed to Chicago physicians and the rest was turned over to the state health department for use throughout Illinois.”

“As was the case with Pfeiffer’s bacillus vaccines, most of the early reports on the use of these mixed vaccines indicated they were effective. Readers of American medical journals in 1918 and for much of 1919 were thus faced with the strange circumstance that all vaccines, regardless of their composition, their mode of administration, or the circumstances in which they were tested, were held to prevent influenza or influenzal pneumonia. Something was clearly wrong. The medical profession had at the time no consensus on what constituted a valid vaccine trial, and it could not determine whether these vaccines did any good at all.”

“McCoy arranged his own trial of the Rosenow vaccine produced by the Laboratories of the Chicago Health Department. He and his associates worked in a mental asylum in California where they could keep all subjects under close observation. They immunized alternate patients younger than age 41 on every ward, completing the last immunization 11 days before the local outbreak began. Under these more controlled conditions, Rosenow’s vaccine offered no protection whatsoever. McCoy’s article appeared as a one-column report in the December 14, 1918, edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).”

“At the meeting of the American Public Health Association (APHA) later that month, McCoy and Park used their positions on the Executive Sub-committee on the Bacteriology of the 1918 Epidemic of Influenza to issue a manifesto that appeared in APHA’s “Working Program against Influenza.” APHA declared that because the cause of influenza was unknown, there was no logical basis for a vaccine to prevent the disease.”

“Perhaps the best evidence that professional standards were changing is found in two studies sponsored by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company during the 1919–1920 influenza season. Both were unprecedented in the influenza literature in the care taken in trial design and analysis. … While adhering to the standards APHA had set forth, both studies concluded the vaccines used were ineffective.”

Recap of the Spanish Flu vaccine list

Here’s a summary of the Spanish Flu vaccines Eyler mentioned, and what little is known about their quantity and distribution. If the vaccines weren’t the product of a deluded anti-vaxxer’s imagination, they would surely number in the millions, perhaps tens of millions.

Bonime vaccine (Physician):

Park vaccine (New York Health Department):

Released to the military for use in Army camps

Released to private physicians

Used as corporate policy among industrial workers, including 14,000 employees of the Consolidated Gas Company and 275,000 employees of the U.S. Steel Company

Leary vaccine (Tufts Medical School, Boston):

Used frequently during the epidemic in state custodial institutions of the Northeast

Used by some private physicians

Pittsburg vaccine (U. of Pittsburgh Medical School Faculty):

Developed a vaccine for the Red Cross in 1 week.

Duval & Harris vaccine (Tulane University Dept. of Pathology and Bacteriology):

Vaccinated approx. 5,000 people, most were employees of large New Orleans companies

Greeley vaccine (Physician, Brooklyn, New York):

Vaccinated his own patients and distributed 8 liters of vaccine to colleagues.

Denver vaccine (Physician in Denver):

Puget Sound vaccine (Puget Sound Naval Yard medical staff):

Used among sailors and civilians in Seattle

Rosenow vaccine (Mayo Clinic Division of Experimental Bacteriology):

Distributed widely to physicians in the upper Midwest

Rosenow received returns for 93,000 people who had received all three injections, 23,000 who had received two injections, and 27,000 who had received one. [352,000 injections]

Adopted by the City of Chicago; Health Department produced more than 500,000 doses of the vaccine that were distributed to physicians and elsewhere in Illinois.

***

NOTES:

(1) Doshi, P., Influenza: marketing vaccine by marketing disease, BMJ 2013; 346 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3037 (Published 16 May 2013) Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f3037

“…even the ideal influenza vaccine, matched perfectly to circulating strains of wild influenza and capable of stopping all influenza viruses, can only deal with a small part of the ‘flu’ problem because most ‘flu’ appears to have nothing to do with influenza. Every year, hundreds of thousands of respiratory specimens are tested across the US. Of those tested, on average 16% are found to be influenza positive.”

(2) Eyler J. M. (2010). The state of science, microbiology, and vaccines circa 1918. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 125 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549101250S306 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/00333549101250S306